During the colder months, the sleepy villages of rural England possess a unique charm that may inspire the great and the good.

“I like this place and willingly could waste my time in it” – (Act II, Scene IV).

“I like this place and willingly could waste my time in it” – (Act II, Scene IV).

Rural England. Winter. The sun does not awake ‘til 8am and then makes matters worse by skipping off early at about 4pm.

Departing Heathrow airport, I am hustled on my way to the country by startled English trees. They are shadows of their naked selves, silhouettes that shiver in the dusk. Binding them are brittle hedges and frigid dry-stone walls, all sucking the heat out of the sky and radiating a kind of marble-like chill.

The grey sky is a low sky, in so much as it appears to have a ceiling. The only reason it is not any lower is because of the need to fit Cavalier King Charles spaniels, lollipop ladies, satanic mills and football in between it and the cold sod. Sod that mires the boots on trips to glowing pubs.

Pubs are sprinkled liberally around England or England is sprinkled liberally around pubs. It’s hard not to love a good village pub, with its warm bitters. In the rural village of Bretforton in the West Midlands, north-west of London, The Fleece Inn has become an attraction in its own right. The picturesque little pub has an impressive heritage, having been owned by the one family since the days of Chaucer. It has now owned by the National Trust but not before someone has seen fit to paint white circles before the hearth thus preventing witches from swooping down the chimney and ruining a ripping game of cribbage. Highly recommend is the game pie.

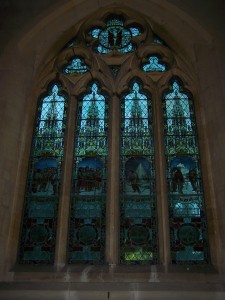

The village of Binton, just to the north-east of Bertforton and west of Stratford-upon-Avon, is worth a look – not least because I was raised there. But being too close to the big picture of figgy pudding that is rural England tends to cloud the beauty and history of the place. Stand a little further back and one can discern Robert Falcon Scott (the lusty adventurer) praying at St Peter’s village church in Binton, praying for a successful outcome to his 1912 South Pole adventure. Alas, there is a stained glass window in memoriam.

The village of Binton, just to the north-east of Bertforton and west of Stratford-upon-Avon, is worth a look – not least because I was raised there. But being too close to the big picture of figgy pudding that is rural England tends to cloud the beauty and history of the place. Stand a little further back and one can discern Robert Falcon Scott (the lusty adventurer) praying at St Peter’s village church in Binton, praying for a successful outcome to his 1912 South Pole adventure. Alas, there is a stained glass window in memoriam.

Opposite the church there is a natural spring that bubbles from the mouth of a bronze lion head. Several decades ago the water was condemned due to something excessive sloshing around – radium or badger’s urine – and a local council health warning was prominently displayed to notify any thirsty itinerant not to quaff of those waters (ah, but they giggle so seductively).

It was not up 24 hours before it was ripped down by some indignant marrow farmer, who had probably been irrigating his champion sprouts with it and was delighted with the results. Funny that the sign was never replaced.

The name Binton may well derive from “Bina’s Ton”. Bina, an Anglo-Saxon property tycoon who owned the village and ‘ton’, antecedent of ‘town’. According to the Domesday Book of 1086, which outlined each English landowner’s land and livestock, Binton had a population of 29 families with 150 people working seven ploughs and three mills.

The population has stayed relatively steady (272 at last count); the homes haven’t changed much either. The house in which I grew up is about 300 years old, built when locals were a mere 5-feet tall, stooped and impoverished with the burden of agricultural work in those days. They built the houses after they had stopped growing and must have thought they were fairly spacious. Few can navigate the house without concussing themselves on a splintered lintel.

The population has stayed relatively steady (272 at last count); the homes haven’t changed much either. The house in which I grew up is about 300 years old, built when locals were a mere 5-feet tall, stooped and impoverished with the burden of agricultural work in those days. They built the houses after they had stopped growing and must have thought they were fairly spacious. Few can navigate the house without concussing themselves on a splintered lintel.

Nearby Welford-on-Avon boasts the tallest maypole in England at 65 feet (20 metres). The original wooden pole was replaced by an aluminium one after a lightning strike. Around this maypole we children, suspended by coloured ribbons, would cavort and inevitably become entangled while dancing jigs like the Merry Swan and the Randy Partridge (sic).

Naturally we had not a clue what we were celebrating – the fecundity of Spring inspired by Germanic paganism.

Many Tudor half-timbered and thatched cottages are dotted around the village and, as luck would have it, three pubs – The Four Alls, The Bell Inn and The Shakespeare Inn.

That’s really let the cat out of the bag. Yes, this is Shakespeare country. Stratford-upon-Avon is not a bodkin’s thrust from Binton and is the birthplace of the immortal playwright, Bill Shakespeare. The villages surrounding the beautiful town made famous by the Bard can be overlooked in favour of Stratford-upon-Avon’s festivals and Olde English theatre but amble through for a taste of where Bill may have found his inspiration.